Early Evidence Links Small Area FMRs and Neighborhood Quality

- Title:

- Early Evidence Links Small Area FMRs and Neighborhood Quality

- Author:

-

Robert Collinson and Peter Ganong

- Source:

-

Working Paper, Harvard Department of Economics

- Publication Date:

-

2014

While housing vouchers can in theory be used to rent privately-owned housing anywhere, the rent must not be appreciably higher than the area’s fair market rent (FMR), as published by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). FMRs are currently set at the metropolitan level for most of the United States, effectively limiting the use of vouchers in average to above-average priced communities. As part of a legal settlement, in 2011 housing authorities in the Dallas, Texas area began using multiple “small area” FMRs attached to each of the city’s ZIP Codes, rather than having a single metropolitan-wide FMR. This could expand the neighborhoods in which voucher holders can find housing, and may also reduce overpayment in lower-cost neighborhoods. In areas where the FMR dropped, a one-year grace period was instituted before the changes were fully in effect.

What effect do small area FMRs have on housing and neighborhood quality for housing voucher recipients? Would voucher-assisted households be as likely to improve their living conditions by increasing HUD’s payment standard to allow rents up to the metropolitan median rather than just up to the 40th percentile?

A working paper available through the Department of Economics at Harvard University, The Incidence of Housing Voucher Generosity, addresses these questions through data on housing rented by families who moved after the adoption of small area FMRs in Dallas and HUD data on FMR “rebenchmarking” that led to increases in the payment standard. By measuring violent crime rates, test scores, poverty rates, the share of single-parent households, and unemployment rates, the researchers created a “neighborhood quality index” that they used to analyze whether or not housing voucher recipients moved to better quality neighborhoods during the pilot program.

Major findings:

- Using a neighborhood quality index, the researchers found that the quality of neighborhoods that voucher recipients moved to rose by .23 standard deviations, a significant improvement. Mobility counseling, which was made available through the same court settlement, does not explain the results as most movers did not receive the counseling.

- The largest difference in neighborhood characteristics for movers was on violent crime rates. Neighborhoods of movers had violent crime rate that were .33 standard deviations lower than prior to the move.

- Combining their analysis with work by Raj Chetty connecting neighborhoods and children’s long-term economic opportunities, they find that movers’ children, at age 30, would have a 4.3 percentage point increase in income rank – reaching the 43rd percentile.

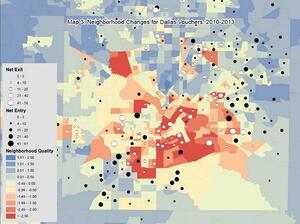

- Spatial analysis shows that upon the change in FMR, net exits were more often from the lowest-quality neighborhoods in southern Dallas with net entries typically higher in moderate-to-high quality neighborhoods further south and to the northeast. (See map above.)

- For voucher holders who moved and were fully subject to the new small area FMRs, there was a substantially increase in the rents paid in more expensive areas, and decrease in rents paid in less expensive areas. Every $1 change in FMR was associated with a 57-cent change in rents among movers, 19 cents of which was attributable to better structural quality of the rented homes.

- The quality of the physical structures being rented by voucher holders rose with FMR increases and fell in areas where the FMR dropped.

- The average rents for movers stayed the same, since many voucher holders rented housing in low-cost neighborhoods.

- When examining a broader rent ceiling increase (without switching to small area FMRs), the authors find it would have minimal effect on the quality of housing rented by voucher holders. For every $1 of additional rent ceiling, rents rose by 41 cents, yet only 5 cents of that can be attributed to quality increases.