Why We Need to Stop Evictions Before They Happen

Eviction is more than a forced move. It’s a destabilizing event that can send a family into a cycle of financial and emotional turmoil, affecting their current and future prospects for residential stability.

Attention around evictions has grown largely because of the work of Matthew Desmond, author of Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City and founder of the Eviction Lab, a team that created the first national dataset of court eviction filings and judgments dating back to 2000. In the community data they could access, Desmond’s team found nearly 900,000 eviction judgments in 2016. Households headed by black women were most commonly affected by evictions.

The database has illuminated a hidden crisis plaguing many US communities, from small rural towns to large urban areas. And it has sparked a discourse among local leaders searching for ways to tailor proactive solutions to their communities and bring their eviction rates down.

Where evictions fit into the greater housing affordability problem

Evictions are a more visible part of a broader residential instability and affordability problem. The inventory of low-cost rental housing continues to shrink, and wait times for rent subsidies sometimes last decades. Only one in five low-income renter households who needs federal rental assistance receives it.

Affordability problems are affecting the broader rental market. More than a quarter of renters,or 11.1 million renter households, are severely cost burdened, meaning they spend more than half their income on rent. And the number of affordable and available units is far less than the needs of extremely low–income households.

“Rental assistance is underfunded. It shouldn’t be surprising that eviction is a problem given that there are so few resources to support people when they’re in crisis,” said Martha Galvez, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute. “Evictions are a component of the larger affordability problem and lack of affordable housing in general.”

Other potential contributing factors to evictions (which vary depending on state and local laws) include a lack of legal protections for renters, nuisance laws that can adversely affect victims of domestic violence, and sudden financial shocks that can result in families being unable to pay their rent.

The consequences of failing to take a proactive approach

"The insidious part of instability is that it comes at a kid from so many different levels-in terms of stress on their parents, losing basic resources, and then losing their homes. It's this very core thing of stability of place, where you'll be sleeping or eating. Housing instability crashes every support system kid could have."

- Gina Adams, senior fellow at the Urban Institute

The aftermath of an eviction can affect all aspects of a family’s life. Families might lose their belongings if their possessions are dumped on the street, they might struggle to find good housing with an eviction filing on their court record, they might need to move to a less safe neighborhood, and kids might need to switch schools midyear. Evictions can also put people’s employment and mental health at risk.

Residential instability can be especially traumatizing for children, with stress having wide-reaching consequences, including on their educational achievement. When children whose families receive housing subsidies live for longer periods in subsidized housing, those children see lower incarceration rates and higher pay as adults.

“The insidious part of instability is that it comes at a kid from so many different levels—in terms of stress on their parents, losing basic resources, and then losing their home,” said Gina Adams, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute. “It’s this very core thing of stability of place, where you’ll be sleeping or eating. Housing instability crashes every support system a kid could have.”

When families struggle financially, so do their communities. The financial health of a city is closely intertwined with that of its residents. Financially healthy residents are better able to weather difficult times, are less likely to need city supports and services, and can contribute more to the local economy by supporting property, sales, and income taxes.

Cities are struggling to keep up with the cost of providing homelessness services to residents, and they miss out on utility bills and property taxes when families are no longer in a home. In Miami, for example, family financial insecurity that leads to eviction and unpaid property taxes and utility bills is estimated to cost the government between $13 million and $31 million annually.

“It’s certainly a better investment to help somebody stay in their housing than let them become homeless,” said Mary Cunningham, vice president for metropolitan housing and communities policy at the Urban Institute. “Once somebody experiences homelessness, it’s really expensive to public systems in terms of cost of shelter and services, and it’s expensive for the people it affects in terms of losing their belongings and having to start over. We want to do everything we can to make sure people have help to stay in their housing.”

"Cities are spending so much money after the fact, when it would be a better investment to spend the money earlier in the process and keep families and communities more stable and see a better return on their money."

- Diana Elliott, senior research associate at the Urban Institute

The Eviction Lab hasn’t released national data on the median cost a family owes to the landlord that results in them getting evicted, but it did find the median amount owed was $686 in Richmond, Virginia. Desmond has said that people in other cities are often evicted for just a few hundred dollars.

“In some cases, cities are spending tens of thousands of dollars per person [for homelessness services, unpaid utility bills, and unpaid property taxes]. Wouldn’t it make sense to make sure people don’t become evicted in the first place?” said Diana Elliott, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute. “Cities are spending so much money after the fact, when it would be a better investment to spend the money earlier in the process and keep families and communities more stable and see a better return on their money.”

Tactics to help solve the eviction crisis

Strategies to tackle the eviction crisis should focus on helping renters avoid falling behind on their rent and reducing the risk of eviction if they do.

“I do not think there is a once-and-for-all solution that does not involve some kind of government or philanthropic assistance to households that are trapped in the cycle of eviction or threatened by eviction for the first time,” said Corianne Scally, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute.

One way to reduce the risk of eviction is to add and retain rental housing that low-income families can afford. That might mean changing the rental subsidy system to regulate rents or offer universal assistance to the lowest-income households, or pairing land-use reforms with increases in rent subsidies.

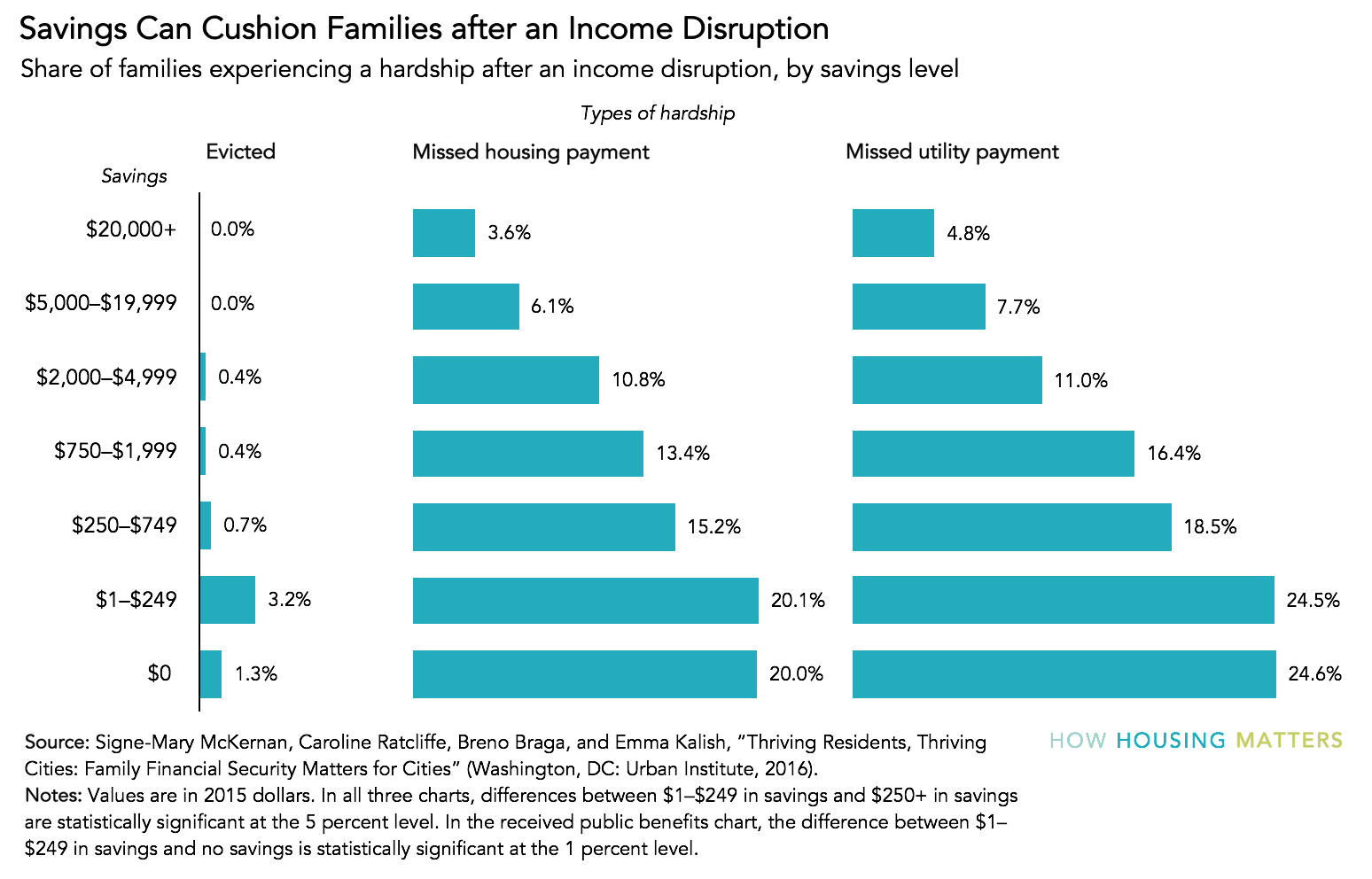

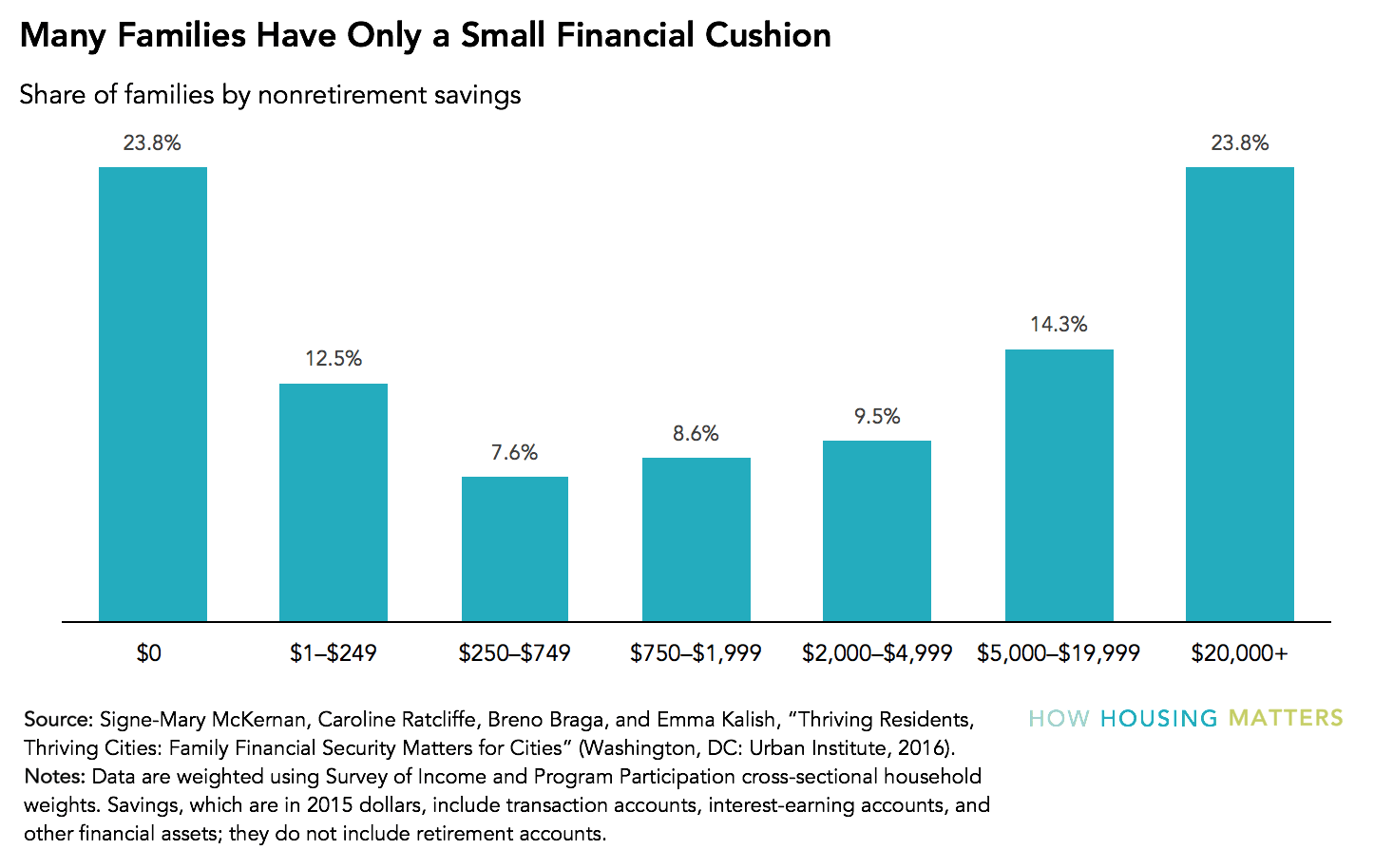

Even modest personal savings can help families become more financially stable and avoid eviction. Urban Institute researchers have found that families with as little as $250 to $749 in savings are better able to weather temporary income drops and are less likely to be evicted or miss a housing or utility payment.

“When we look at the relationship with family financial health measured by savings and debt and outcomes that matter for cities (such as eviction and the ability to pay rent or mortgage), we find increased financial health associated with decreased evictions, fewer missed housing payments, and a greater ability to pay utility bills,” said Signe-Mary McKernan, vice president for labor, human services, and population at the Urban Institute.

Cities can improve their residents’ financial health through broad-based strategies from workforce development to affordable housing and through programs and policies that focus directly on residents’ financial health. These focused approaches include helping residents save through savings programs with incentives, integrating financial and savings interventions into existing programs and platforms, and providing financial coaching and counseling.

But those long-term solutions don’t help families facing eviction now. No community has enough rental options that people can afford, and more than one-third of US families have less than $250 in savings.

When families fall behind on rent, emergency assistance programs can help them pay the past-due balance to prevent eviction. Because eviction rules and risks vary, local jurisdictions should tailor solutions specific to their residents’ challenges, said Leah Hendey, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute and codirector of the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership.

Legal assistance for low-income renters—either through expanded legal aid resources or a right to counsel—can also improve outcomes for renters and reduce evictions.

Nearly 99 percent of landlords appearing in New York City's housing courts were represented by attorneys in 2017, compared with only 27 percent of tenants.

A New York City Office of Civil Justice survey found that tenants in housing court who received an attorney from a legal aid provider were twice as likely to keep their home, compared with tenants who did not receive one.

In 2017, New York City passed legislation guaranteeing legal representation for low-income tenants who face eviction, the first legislation of its kind in the US. And last month, San Francisco voters approved a measure providing a lawyer for every city tenant facing potential eviction.

“Policy changes have been coming down the pipeline over the past few years, and there is some momentum growing where jurisdictions recognize that if they want to have an inclusive city, they need tenant protections and antidisplacement strategies, and protection from eviction is crucial,” Cunningham said.

Maya Brennan, Kimberly Burrowes, Veronica Gaitán, David Hinson, Jerry Ta, John Wehmann, and Daniel Wood of the Urban Institute contributed to this feature.

Photo by Vincent Noel/Shutterstock