(kate_sept2004/Getty Images)

Housing Market Researchers Tend to Ignore Co-Borrower Race. Differences In Denial Rates Suggest They Shouldn’t.

This post was originally published on Urban Wire, the blog of the Urban Institute.

Racial disparities in the housing market are well documented. Large homeownership rate gaps between Black and Latinx households and white households persist mostly unchanged since the 1960s, when race-based housing discrimination was legal. Evidence shows that Black and Latinx mortgage applicants are denied at higher rates than white applicants, even when controlling for borrower characteristics, a discrepancy that is driven in part by the systemic disadvantages created by a legacy of racist housing and credit legislation.

But most research on racial disparities in the housing market defines race and ethnicity according to the identity of the primary borrower or head of household, ignoring coapplicants or coheads of household. When the race and ethnicity of both borrowers is included, we find that households where the coheads have different racial or ethnic identities have distinct outcomes in the mortgage market, with their denial and homeownership rates falling between that of dual-white households and dual-Black or dual-Latinx households, regardless of which member is tagged as the primary applicant or head of household.

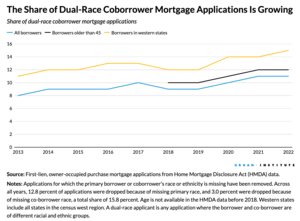

With the share of dual-racial and dual-ethnic households continuing to grow in the US, dual-race or dual-ethnicity coborrowers are becoming a larger share of mortgage applications, especially among younger borrowers and borrowers in western states. A vast majority of dual-race coborrower pairs include one white borrower. As a result, relying solely on the primary borrower’s race and ethnicity will increasingly distort our understanding of the housing market. Throughout this post, we use “dual race” for applications and households when referring to dual applicants and coheads of households of different racial and ethnic groups.

What we know, and don’t know, about dual borrowers

Prior research suggests that solo applicants are denied at higher rates than dual applicants, even with controls. A recent study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis found that Black and Latinx applicants are more likely than their white counterparts to apply solo.

But little work has been done to understand the effects of ignoring the coborrower or cohouseholder’s race and ethnicity. Consumer Financial Protections Bureau reports include a few statistics on a “joint” applicant category (defined as one white applicant and one applicant of color) but does not break out the race and ethnicity of the coborrower. Because the “joint” group definition includes exclusively applications with dual borrowers, it’s misleading to compare these with statistics from groups that include solo borrowers.

By including the coborrower’s race and ethnicity, we see significant differences in the denial and homeownership rates, which raises questions about how coborrower race should be included in future research. In the analyses below, we exclude solo-applicant and single-headed households to give an apples-to-apples comparison.

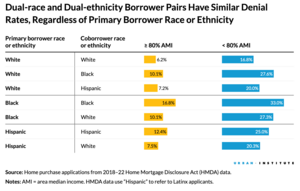

Dual-race borrower pairs have higher denial rates than white borrower pairs

When looking only at the primary borrower’s race and ethnicity, white two-borrower applications have lower denial rates than Black and Latinx two-borrower applications. Because denial rates are highly correlated with income across racial and ethnic groups, we also separated groups into those earning above and below 80 percent of the area median income. But when we introduce coborrower race and ethnicity, the story is not so straightforward.

Current racial definitions would classify white primary applicants with Black or Latinx co-applicants simply as “white applicants,” but the denial rates for these borrowers are essentially the same as those for Black or Latinx primary applicants with white co-applicants. These results are clear: race and ethnicity matter in the mortgage market and not just for the primary applicant.

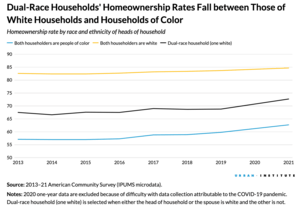

Dual-race households have lower homeownership rates than white households

Homeownership rates follow a similar pattern. The Census Bureau reports homeownership numbers using the head-of-household definition in its summary tables, making it simple for researchers and policymakers to see homeownership rates by race and ethnicity. But as the share of dual-race households increases, our current understanding of racial homeownership gaps may not be accurate.

Households for which the head and their spouse were white have the highest homeownership rates (upward of 80 percent). Meanwhile, households of color have much lower homeownership rates (around 60 percent since 2013). Dual-race households for which either—but not both—the householder or the spouse is white had a homeownership rate that fell between the two. These data suggest that our current understanding of racial homeownership gaps may not be accurate, and it may be growing more inaccurate annually, as the share of dual-race households grows.

Analysis should consider including these breakouts

The potential implications of these data require further study, but there are situations where ignoring the coborrower could seriously obfuscate results. In metropolitan areas where interracial marriage is more common, for example, current methods could be downplaying racial disparities if coborrowers of color are being counted as white. And in the western US, a greater share of households are dual-ethnicity; ignoring these households could result in a systemic underestimate of Latinx homeownership activity.

Simplification and streamlining are sometimes necessary to make research products readable and clear, but researchers should consider the effects of aggregating the primary borrower’s race and ethnicity. Researchers may want to define race differently for different bodies of work to accurately inform state and local policy.

As the mortgage market shifts to include more dual-race borrower pairs, differences in results because of racial and ethnic categorization will become only more significant. All researchers should be clear about how they have defined race and ethnicity in their publications to produce clarity, consistency, and better understanding.